The smoke stacks for the Tennessee Valley Authority’s steam generation plant lord over the part of Muhlenberg County once known as Paradise. In a great ironical twist, the steam plant now carries the name “Paradise.” Today, when a soul is in Paradise, he cannot escape the omnipresent concrete and steel exclamation points that jab their way into the Kentucky sky. They are the megalo-modern world’s exclamation, shouting over a world long since gone. Orangish yellow smoke and white steam rush from the tops of those stacks into the blue sky, reminiscent of when a booted foot stirs the silt from the bottom of a clear flowing creek. Only in Paradise, the image is inverted. The choking haze leaps into the sky above everything and everyone.

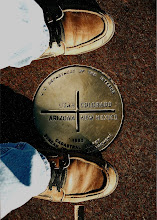

A few years ago, my wife and I were twiddling our way through the Green River Valley killing a day off from work. At some point we found a large official looking sign proclaiming in large letters “TVA PARADISE.” I snapped a photograph of Dana standing in front of the sign. In the photo she is braced against the wind and her hands are pulling the collar of her raincoat up around her neck. Behind the sign the TVA plant smokes and steams in a cold autumn rain. A rain drop splattered the camera’s lens just as I triggered the shutter, as if a tearful angel somehow tried to stop me from documenting a lost Paradise.

I could not resist the bleak poetry of the image before me. Paradise. It seemed to prove the truism Don Henley professed in the Eagles’ song Providence, “you call someplace paradise, kiss it goodbye.”

Paradise was a real place at one time. Legend states that a young couple traveling the Green River with their hopelessly sick child woke to discover the baby had regained its health. Allegedly one of them proclaimed, “This truly must be Paradise.” It is not important how Paradise got its name. There is little doubt that this idyllic little town was a paradise to the people of that part of Muhlenberg County before the destructive hand of the modern world clenched its fist around that blissful place. It overlooked a ferry crossing on Green River from a knoll once topped with houses, stores, trees, and people.

The little town probably owed its life, at least its heyday, to the extraction of minerals from the Muhlenberg countryside. Ironmasters and miners flocked to Paradise to capitalize on the precious minerals tucked in black veins beneath the life giving land.

Scottish immigrants bankrolled by the limitless wealth of Robert Sproule Crawford Aitchison Alexander failed at smelting iron ore into even greater wealth a mile down stream at Airdrie Hill. R.S.C.A. Alexander was descended from Scottish kings, and only royal blood could carry around that many names. The Alexander family is more famous for the Airdrie Stud Farm in Woodford County, a place where their descendants still lord over the land.

Later, General Don Carlos Buell came to Paradise. In the Civil War the priggish little general achieved fame when he saved Ulysses S. Grant’s forces at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. Later, however, Buell’s reluctance or inability to pursue Confederate forces after the Battle of Perryville in Boyle County resulted in the army removing him from command. Many contended that the career soldier was a Confederate sympathizer, and although an investigative committee cleared his name, the taciturn man resigned his commission.

In 1866, Buell came to Muhlenberg County in search of oil and leased thousands of acres at Airdrie Hill near Paradise to search for it. Buell never found oil, and one could contend that he never found his own paradise. After coming up dry in the oil business, he started a coal mining operation at Airdrie, which was successful for a number of years, but even in that business Buell found only anguish. In 1868, the Kentucky General Assembly chartered the “Green and Barren River Navigation Company” and charged it with keeping the river and locks open to navigation. The company managed the river with great zeal, quickly discovering its own power as a monopoly. Their high freight rates and unfair business practices soon forced Buell’s company to near insolvency. By the 1880’s, Airdrie produced no coal, and the paradise Buell sought there turned into a hellish denouement for an old general.

The black veins remained under Paradise. Everyone knew what was beneath the ground under their feet, but they had no way of knowing that the future held anguish for their locality. The seams of coal beneath the area were three and six feet thick and posed problems for underground mining. It was not until the 20th Century that man created an efficient way to extract the coal in eastern Muhlenberg County. Mining companies used massive machines to gouge through the land, which they carelessly called “overburden,” to get to the black veins below. Iron claws powered by steam, Diesel, and electricity gnawed at the Muhlenberg countryside for decades leaving behind a tormented landscape and a little fragment of Paradise. Then, Paradise sat by itself along Green River and its kinsman, the iron furnace, stood as a stony skeleton beneath a mined out rise once called Airdrie Hill.

The modern world was not through with Paradise. In 1962, the TVA began constructing the Paradise Steam Generation Plant, which, for a time, co-existed with the paradisiacal little remnant of Muhlenberg’s past. Angst filled the co-existence, though. The few people left in Paradise found the belching smokestacks and the endless delivery of coal to fulfill the world’s insatiable appetite for electricity to be unbearable.

In 1967, the TVA purchased Paradise and removed all of its inhabitants. Then, it allowed the Pittsburgh and Midland Mining Company to bring in their heavy equipment and towering shovels and punishing drag buckets to strip out Paradise for the black coal beneath it. The very thing that had once provided life for Paradise now killed it.

People continuously try to blame the TVA, P&M Mining, and the Peabody Coal Company for the loss of Paradise. We can very well blame their attitudes, but it is impossible to place it entirely on them without also looking at the sum of the world in which we live, the world man has created for himself.

Do we not use up a little bit of Paradise each time we flip on a light bulb or boot up a computer?

Yep. “You call some place paradise, kiss it goodbye.”

A few years ago, my wife and I were twiddling our way through the Green River Valley killing a day off from work. At some point we found a large official looking sign proclaiming in large letters “TVA PARADISE.” I snapped a photograph of Dana standing in front of the sign. In the photo she is braced against the wind and her hands are pulling the collar of her raincoat up around her neck. Behind the sign the TVA plant smokes and steams in a cold autumn rain. A rain drop splattered the camera’s lens just as I triggered the shutter, as if a tearful angel somehow tried to stop me from documenting a lost Paradise.

I could not resist the bleak poetry of the image before me. Paradise. It seemed to prove the truism Don Henley professed in the Eagles’ song Providence, “you call someplace paradise, kiss it goodbye.”

Paradise was a real place at one time. Legend states that a young couple traveling the Green River with their hopelessly sick child woke to discover the baby had regained its health. Allegedly one of them proclaimed, “This truly must be Paradise.” It is not important how Paradise got its name. There is little doubt that this idyllic little town was a paradise to the people of that part of Muhlenberg County before the destructive hand of the modern world clenched its fist around that blissful place. It overlooked a ferry crossing on Green River from a knoll once topped with houses, stores, trees, and people.

The little town probably owed its life, at least its heyday, to the extraction of minerals from the Muhlenberg countryside. Ironmasters and miners flocked to Paradise to capitalize on the precious minerals tucked in black veins beneath the life giving land.

Scottish immigrants bankrolled by the limitless wealth of Robert Sproule Crawford Aitchison Alexander failed at smelting iron ore into even greater wealth a mile down stream at Airdrie Hill. R.S.C.A. Alexander was descended from Scottish kings, and only royal blood could carry around that many names. The Alexander family is more famous for the Airdrie Stud Farm in Woodford County, a place where their descendants still lord over the land.

Later, General Don Carlos Buell came to Paradise. In the Civil War the priggish little general achieved fame when he saved Ulysses S. Grant’s forces at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. Later, however, Buell’s reluctance or inability to pursue Confederate forces after the Battle of Perryville in Boyle County resulted in the army removing him from command. Many contended that the career soldier was a Confederate sympathizer, and although an investigative committee cleared his name, the taciturn man resigned his commission.

In 1866, Buell came to Muhlenberg County in search of oil and leased thousands of acres at Airdrie Hill near Paradise to search for it. Buell never found oil, and one could contend that he never found his own paradise. After coming up dry in the oil business, he started a coal mining operation at Airdrie, which was successful for a number of years, but even in that business Buell found only anguish. In 1868, the Kentucky General Assembly chartered the “Green and Barren River Navigation Company” and charged it with keeping the river and locks open to navigation. The company managed the river with great zeal, quickly discovering its own power as a monopoly. Their high freight rates and unfair business practices soon forced Buell’s company to near insolvency. By the 1880’s, Airdrie produced no coal, and the paradise Buell sought there turned into a hellish denouement for an old general.

The black veins remained under Paradise. Everyone knew what was beneath the ground under their feet, but they had no way of knowing that the future held anguish for their locality. The seams of coal beneath the area were three and six feet thick and posed problems for underground mining. It was not until the 20th Century that man created an efficient way to extract the coal in eastern Muhlenberg County. Mining companies used massive machines to gouge through the land, which they carelessly called “overburden,” to get to the black veins below. Iron claws powered by steam, Diesel, and electricity gnawed at the Muhlenberg countryside for decades leaving behind a tormented landscape and a little fragment of Paradise. Then, Paradise sat by itself along Green River and its kinsman, the iron furnace, stood as a stony skeleton beneath a mined out rise once called Airdrie Hill.

The modern world was not through with Paradise. In 1962, the TVA began constructing the Paradise Steam Generation Plant, which, for a time, co-existed with the paradisiacal little remnant of Muhlenberg’s past. Angst filled the co-existence, though. The few people left in Paradise found the belching smokestacks and the endless delivery of coal to fulfill the world’s insatiable appetite for electricity to be unbearable.

In 1967, the TVA purchased Paradise and removed all of its inhabitants. Then, it allowed the Pittsburgh and Midland Mining Company to bring in their heavy equipment and towering shovels and punishing drag buckets to strip out Paradise for the black coal beneath it. The very thing that had once provided life for Paradise now killed it.

People continuously try to blame the TVA, P&M Mining, and the Peabody Coal Company for the loss of Paradise. We can very well blame their attitudes, but it is impossible to place it entirely on them without also looking at the sum of the world in which we live, the world man has created for himself.

Do we not use up a little bit of Paradise each time we flip on a light bulb or boot up a computer?

Yep. “You call some place paradise, kiss it goodbye.”

No comments:

Post a Comment